Rare

Sharon F

I'm Sharon, I have a daughter with epilepsy and a severe learning disability. I blog about our livewire life.

My child has a rare condition. It is called Lennox Gastaut Syndrome (LGS) but it’s even rarer than that, her LGS is caused by a genetic alteration that’s super rare (my words, not the medical term).

I managed to track down a global Facebook group for the gene about four years ago. Last time I checked there were 97 members, worldwide. That’s obviously not everyone, but it gives an indication of how unusual this is. The children in the group all present very differently, so within this we feel rarer still.

If you are not in the disability community, it can be hard to imagine that a child could have something so rare and complex that modern medicine is just not cutting it when it comes to treatment.

My daughter’s main symptom is seizures.

All types - big violent ones, long ones, drop ones, eye fluttery ones; none of these are medical terms but they help to describe them more effectively for people that are not part of the epilepsy community.

We are regularly asked by new people, often in disbelief when I explain how many seizures she suffers through, why there is not an effective treatment and if she will grow out of it. The answer to the second question is easy – no. She has a lifelong genetic condition and hers is not an epilepsy that gets better with age, sadly.

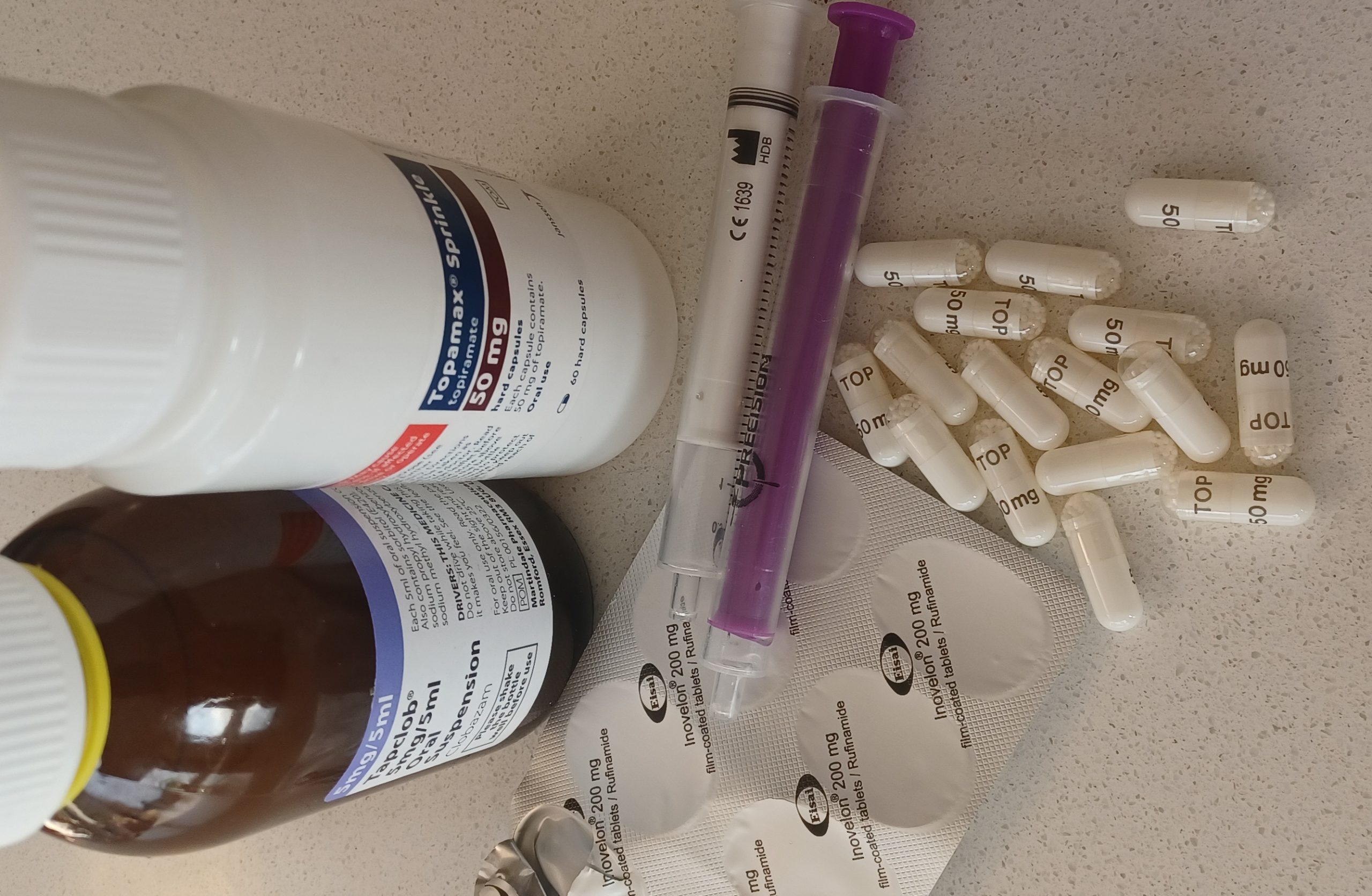

The first question however – often accompanied by the phrase ‘surely something can be done’ is a sobering reminder that we, as humans, know so little about the brain. We have a series of drugs (she’s on 4 at the moment but has tried around 10) but all are blunt instruments that are hard to evaluate when it comes to their efficacy.

We have a Vagus Nerve Stimulator (stimulates the vagus nerve which goes to her brain) which sounds whizzy and technical but again, we don’t know how much it helps. She is also on a medically-prescribed ketogenic diet.

Essentially, we’ve thrown the book at it and she still has seizures, lots of them.

Who knows, maybe if she was on no therapies she may be better, or, perhaps they are helping lots and she’d be having hundreds more seizures if she was on nothing. We don’t know, and we can’t easily test it. Rocking the boat is too terrifying and we’ve been in many worse places that we are now. So we have to plod along and keep trying with the fairly basic tools we have in front of us.

The challenge with rare conditions is that often, very little research is available on the very specific condition. There is often a lot more for a broader condition, in our case epilepsy, but epilepsies, and individual brains, have vast and intricate differences which means what works for some, may be disastrous for another.

It’s essentially a guessing game at this stage, with a bit of gut feeling for good measure.

When you sit alongside consultants and the next move in the game is a joint decision between all of you, things feel different. In some ways this feels good, you are heard as a parent; in others it feels terrifying as our unique child has touched the boundaries of medical science. Let’s hope that the future pushes that boundary further for the next generation of children with rare conditions.